Vanishing Memories

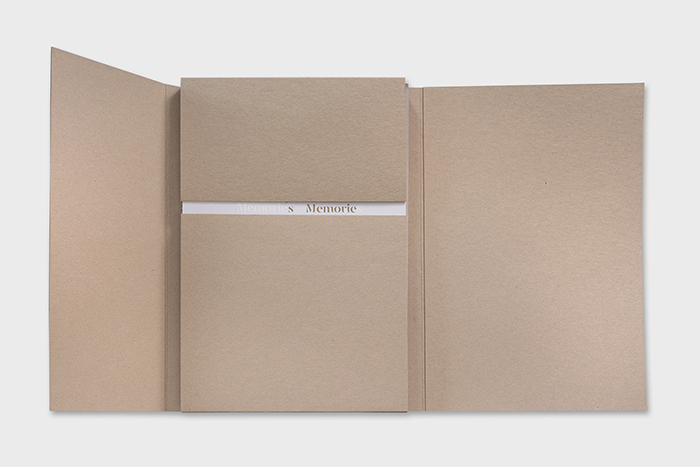

Artists' book published in 2020 by Editions Take5 (Geneva).Potographs

Sixteen original signed photographs by Joan Fontcuberta

Texts

Night opens its Eyes in Us By Zeno Bianu

Learning to Shine By Zeno Bianu

Vanishing Memories by Joan Fontcuberta

The Practice of Kintsugo by Céline Fribourg

Graphic Design

By Romain Rachlin for Les Graphiquants

Printed by Imprimerie du Marais on Japanese papers

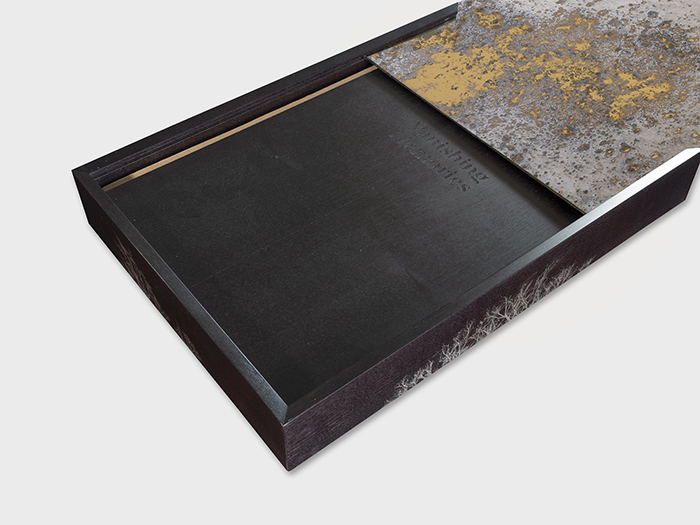

Try case

Designed by the editor and the artist,

Engineered and handcrafted by Jérôme Blanc

Unique mirros with random mercury patterns, glos ans silvery sheens,

made by hand in Great Britain and tinted maple wood tray case inlaid with tin drawings by Jérôme Blanc

Dimensions: 46 x 32x 6,5 cm.

Each of the thirty copies of the edition is numbered, and signed by the artists

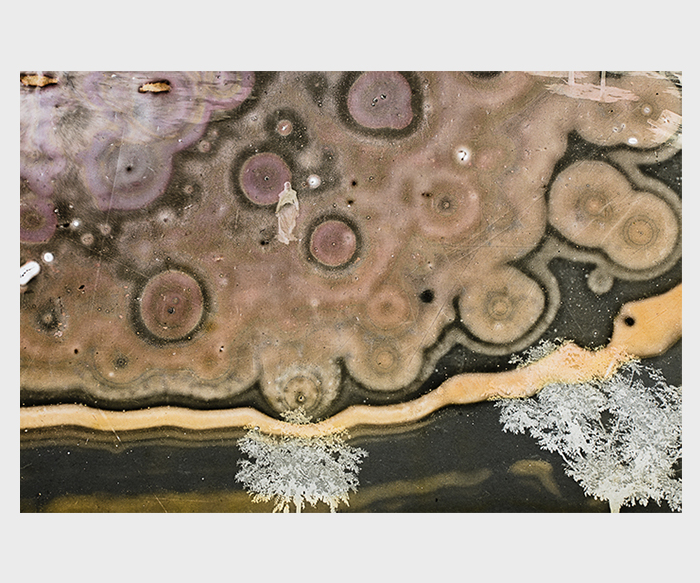

Over several decades, Joan Fontcuberta, who traverses the fields of art and photography, has been developing a critical body of work regarding the relation of photography to verisimilitude, its power of conviction and documentary authority.

In his Vanishing Memories, a dialectic is developed between images lost and found, in an imaginary journey through the space and time of memory.

Fontcuberta uses archive photographs. Damaged by humidity, fungus or bacteria, they show scenes or portraits transformed by the relentless passage of time into abstract landscapes. They give glimpses of mysterious, intriguing or equivocal situations in evanescent images that evade us, exemplifying a way of life that has disappeared for good – one that we scarcely recall, do not recognise, and will never see again. This Trauma of the decomposition of the image, the breakdown of its role as a witness, is the final breath of representation, deficient memory, a ghostly imprint. These photographs highlight the precariousness of our lives and the transience of our memories. Historically, photography has been the pre-eminent instrument of commemoration and elegy, promising a certain form of immortality. But while its infallible character has been called into question over the years on account of its materiality, it retains a particular power: it remains open to interpretation, and to multiple acts of decoding.

It is from this viewpoint that Joan Fontcuberta "resuscitates" archive images, and gives them "a new life". Distorted by nature to the point of negating their primary function, they conserve their fundamental value by turning into tableaux vivants. They become meditative landscapes that reflect our metaphysical quest.

What remains of those we have loved? And what of the traces they have left – are they reliable? Do they disintegrate with the passage of years or our mental projections?

If these images gradually elude us, can traumatic memories be erased and repaired?

In the text he wrote for the book, Fontcuberta goes farther, infusing photographs with soul. And photographs are of course repositories of memory, whether individual or collective. Is their alteration over time not a form of rebellion against something too painful or violent? Digital photography demonstrates the tenuous nature of silver-based prints. We are inundated by images that take over our lives in the instantaneous and the ephemeral.

But the new technologies of the image have not generated the same degree of attachment to the trace as did their predecessors. And today we are seeing a form of nostalgia for "material" images, the process of whose creation brings to mind the maternal womb.

This respect and nostalgia for images damaged by time cannot but recall the ancestral, artisanal, Japanese Kintsugi technique for the repair of broken ceramic objects.

Instructions for a philosophical construction outside of space and time is a poetic and meditative guide to the practice of Kintsugi, an invitation to accommodate flaws and salve wounds. Breakage is repaired and sublimated with a seam of gold so as to magnify rather than dissimulate it.

Symbolically, this means going beyond traumatism into resilience. As a spiritual practice, it is not intended to supply a response to our pain and confusion. Quite the contrary, our sufferings, our emotions are perceived as pathways to an infinite rediscovery of ourselves. Kintsugi constitutes a patient sedimentation of each instant, an eternal return to consciousness that accepts the unpredictability of the world.

Zéno Bianu's poems "Despair doesn't exist" and "Learning to shine" are intensely involved with the pendulum of life. They amplify the wager of transforming the worst case scenario into a force for ascension, the keeping of a promise and a continuance of breath. In a period doomed to dereliction and hypnotic renunciation, Bianu's words shine out as a fracture – a magical, luminous submersion.

This is a mirror-book, suspended, subjecting the reflections of our faces to the distorting mercurial and golden meanders of the mirror, symbolising the passage of time.

These texts and photographs are housed in a mirror-like box. Readers are invited to plunge into it, not just to probe it from outside. They contemplate their images as though they too had been deformed by the vagaries of time, emblematised by the gold and silver twists and turns of the reflective surface. The ramifications of time are symbolised by silhouettes of pewter trees outlined in marquetry on the beechwood frame, which soar up toward the nebulous surface of the mirrors. Is photography itself not a "mirror with a memory"?

FR

FR